Few people know about the old Titan I missile silos that were operational in the early 1960′s. Lowry hosted the first Titan I ICBM missile site located on the bombing range east of Denver. This was conveniently close to the Titan I’s manufacturer, the Martin Company (now Lockheed Martin) located in Littleton, Colorado. The Titans were operational from 1962 to 1965. On March 13, 1958, the Air Force Ballistic Committee approved the selection of Lowry to be the first Titan I ICBM base. Construction of launchers and support facilities began on May 1, 1959. Deployment of the missiles entailed a 3 x 3 configuration, meaning that each of the three complexes had three silos grouped in close proximity to a manned launch control facility. The Omaha District of the Army Corps of Engineers contracted a joint venture led by Morrison-Knudsen of Boise, Idaho, to construct the silos.

Few people know about the old Titan I missile silos that were operational in the early 1960′s. Lowry hosted the first Titan I ICBM missile site located on the bombing range east of Denver. This was conveniently close to the Titan I’s manufacturer, the Martin Company (now Lockheed Martin) located in Littleton, Colorado. The Titans were operational from 1962 to 1965. On March 13, 1958, the Air Force Ballistic Committee approved the selection of Lowry to be the first Titan I ICBM base. Construction of launchers and support facilities began on May 1, 1959. Deployment of the missiles entailed a 3 x 3 configuration, meaning that each of the three complexes had three silos grouped in close proximity to a manned launch control facility. The Omaha District of the Army Corps of Engineers contracted a joint venture led by Morrison-Knudsen of Boise, Idaho, to construct the silos.

A 144-day steel strike in 1959 caused delays and forced Morrison-Knudsen to resort to winter concreting. Despite this problem and others caused by constant design modifications, Morrison-Knudsen completed the project on time with the lowest construction costs of any ICBM base in the country at the time. Fairly smooth management-labor relations contributed to the success. The project also maintained the best safety record in the missile construction program up until that time. Use of a safety net was credited with saving many lives. Three workers did die during the project, although one of these deaths was the result of a motor vehicle accident that occurred off site.

The Lowry AFB Titan I Missile Complex IA is located approximately 15 miles southeast of Denver, Colorado, Township 5 South, Range 65 West of the Sixth Principal Meridian, Section 5, Arapahoe County. The missile complex is located in the center of the 442-acre missile site. The complex is bounded by a chain-link fence and contains approximately 36 acres. An access road (approximately one half mile long) runs from Quincy Ave. north to the missile site. The missile site is situated on a hilltop. Vegetation consists of a few trees and native grasses.

The map ID you have entered does not exist. Please enter a map ID that exists.

Prior to construction of the Titan I Missile Complex the property was part of the Lowry Bombing Range. The 59,814 acre bombing range, operated from 1 July 1952 to 31 December 1952, was used by the local Navy, Lowry Air Force Base, and the Air National Guard for practicing bombing and strafing missions and for demolition of unusable Air Force munitions.

The bombing range was decontaminated (visually searched) and cleared for unrestricted use in May 1963. Since the Titan I Missile Complexes were already completed at that time, they were not searched and subsequently have not been cleared. Titan I Missile Complex 1A is located in the northwest corner of the bombing range. Since construction of the Missile Complex involved extensive excavation, and the target area of the bombing range was approximately four miles southeast of the Missile Complex, it is unlikely that any unexploded ordnance would be present at the site today.

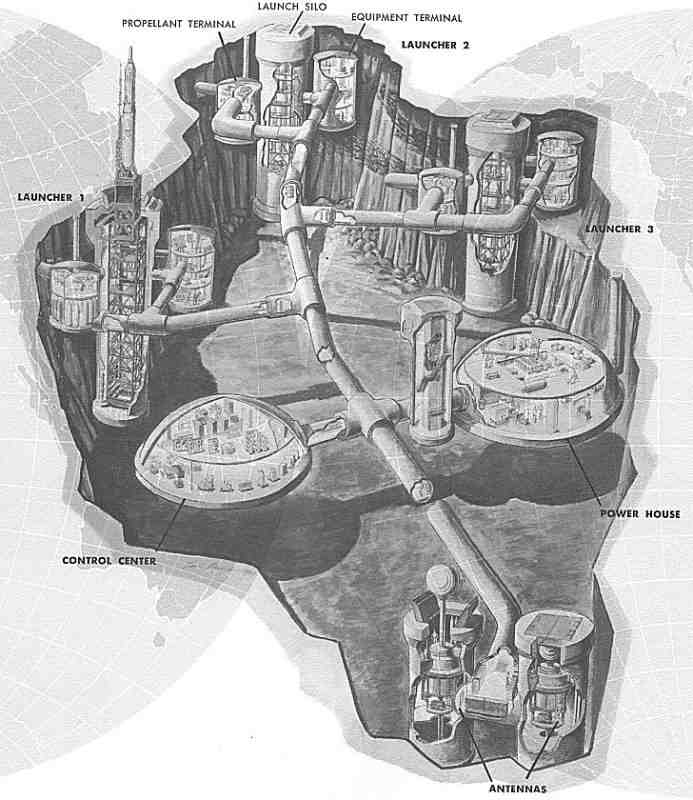

In September 1958, construction began on Titan I Missile Complex 1A, the first of six complexes constructed within an 18 mile radius. The excavation was started in May 1959 using an open cut method with depths ranging from 38′ to 72′. The missile silo shafts were excavated by mining crews to a depth of 163′. The construction of the underground facilities were of reinforced concrete and structural steel with steel lined tunnels. An unusual requirement was the blast-proofing of elements incorporated into the work with the major mechanical and electrical elements shock-mounted to withstand all explosions except a direct hit. The heavy construction phase was completed on 4 June 1961.

The complex was made up of three missile launching silos. The complex is made up of the following: (1) Three launch stations, each with a missile silo, supporting equipment terminal, propellant terminal and propellant system. (2) One guidance facility with two antennas and one antenna (3) One underground control center. (4) Utility and service facilities, including an underground powerhouse for the electrical generating, heating, ventilating, and air conditioning equipment. (5) Interconnecting tunnels for utility distribution and personnel access. (6) Utilities, including roads, water storage and distribution, sanitary system, exterior lighting, portal, air intake, and exhaust. (7) Water wells to provide all water for operation. (8) Access road and perimeter fence.

The missile complex borders the Lowry Landfill to the west. The Lowry Landfill is owned by the city of Denver and is a known source of pollution of the Dawson and Denver Aquifers. The landfill was placed on the national priority list in 1984 under Superfund legislation. The missile complex has three launch silos which penetrate the ground to a depth of 160 feet The activation of the 848th SMS at Lowry Air Force Base on February 1, 1960, marked the first stand-up of a Titan I Squadron. Construction on all nine silos at the three launches complexes for the former 848th, redesignated the 724th, was completed by August 4, 1961. On 18 April 1962, Headquarters SAC declared the 724th SMS operational, and 2 days later the first Titan Is went on alert status. A month later, the sister 725th SMS (initially designated the 849th SMS) declared it had placed all nine of its Titan Is on alert status, which marked a SAC first. Both the 724th and 725th Strategic Missile Squadrons formed components of the Lowry-headquartered 451st Strategic Missile Wing.

On November 19, 1964, Defense Secretary McNamara announced the phase-out of remaining first-generation Atlas and Titan I missiles by the end of June 1965. This objective was met; on June 25, 1965, the 724th SMS and 725th SMS were inactivated. SAC removed the last missile from Lowry on April 14, 1965.

Fetching directions......

Few people know about the old Titan I missile silos that were operational in the early 1960′s. Lowry hosted the first Titan I ICBM missile site located on the bombing range east of Denver. This was conveniently close to the Titan I’s manufacturer, the Martin Company (now Lockheed Martin) located in Littleton, Colorado. The Titans were operational from 1962 to 1965. On March 13, 1958, the Air Force Ballistic Committee approved the selection of Lowry to be the first Titan I ICBM base. Construction of launchers and support facilities began on May 1, 1959. Deployment of the missiles entailed a 3 x 3 configuration, meaning that each of the three complexes had three silos grouped in close proximity to a manned launch control facility. The Omaha District of the Army Corps of Engineers contracted a joint venture led by Morrison-Knudsen of Boise, Idaho, to construct the silos.

Few people know about the old Titan I missile silos that were operational in the early 1960′s. Lowry hosted the first Titan I ICBM missile site located on the bombing range east of Denver. This was conveniently close to the Titan I’s manufacturer, the Martin Company (now Lockheed Martin) located in Littleton, Colorado. The Titans were operational from 1962 to 1965. On March 13, 1958, the Air Force Ballistic Committee approved the selection of Lowry to be the first Titan I ICBM base. Construction of launchers and support facilities began on May 1, 1959. Deployment of the missiles entailed a 3 x 3 configuration, meaning that each of the three complexes had three silos grouped in close proximity to a manned launch control facility. The Omaha District of the Army Corps of Engineers contracted a joint venture led by Morrison-Knudsen of Boise, Idaho, to construct the silos.